MPB Meets: Climate Crisis Photographer Ragnar Axelsson

Published 19 December 2024 by MPB

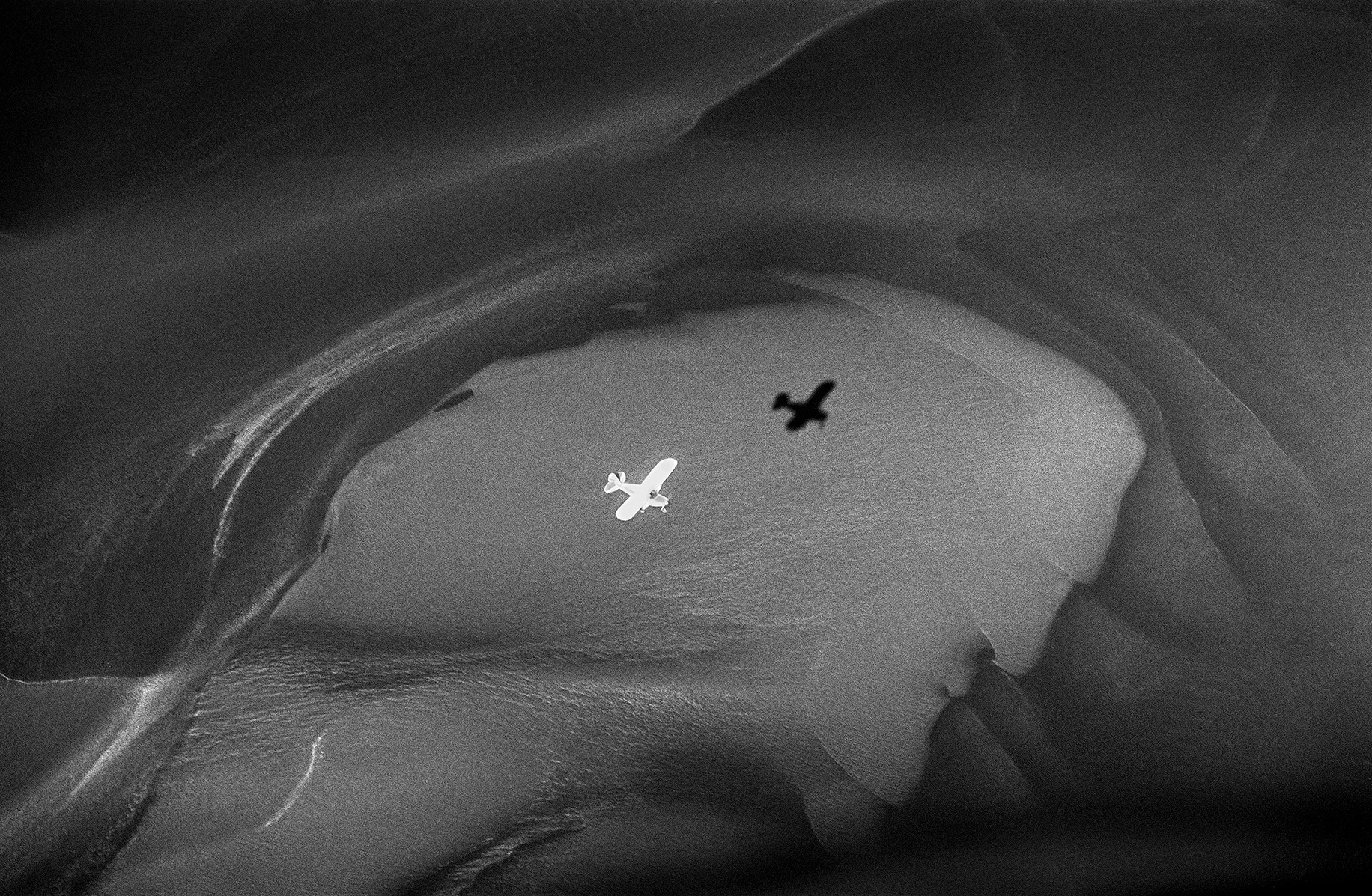

With a career spanning over forty years, Ragnar Axelsson is one of the best-known photographers of the Nordics. His stunning black-and-white photography, which captures the beauty and fragility of the Arctic, has won dozens of awards, published in nine books, and featured in magazines and exhibitions around the world. Ragnar Axelsson’s photography is particularly celebrated for its documentation of the dramatic effects of the climate crisis.

Between 1976 and 2020, Ragnar Axelsson was a photojournalist for Iceland’s most popular newspaper, Morgunblaðið. And, for his Arctic photography, Ragnar Axelsson has received the Order of the Falcon (Knight’s Cross), the highest award Iceland bestows on its citizens. Ragnar Axelsson’s MPB-sponsored retrospective, Where the World is Melting, features his stunning images of people, animals and places in Iceland, Greenland, Siberia and beyond.

In this interview, Ragnar Axelsson shares his experience growing up in Iceland, his passion for photography and the role photographers can play in raising awareness of the climate crisis. Read on to hear from Ragnar and check out his work below.

MPB: What inspired you to become a photographer?

RA: I started taking photos with my father's camera when I was eight. I grew up on a small, isolated farm on the south coast of Iceland. I had a great time there. Taking pictures of the people on the farm, the birds, the landscapes and the glaciers was great fun for me. That magical moment when you see the developed images for the first time—that's something you want to do again and again in the future.

MPB: So you started with analogue photography and then switched to digital photography?

RA: I still do both. These days, digital cameras are so good. But I started in darkrooms with film. The first time I was in Greenland for three weeks, and it took a month afterwards to develop the film. It's like waiting for Christmas presents. And you always ask yourself whether the pictures turned out at all. With a digital camera, I can see that right away.

MPB: Was it always clear that you wanted to be a photographer?

RA: I wanted to be a pilot and also learned to fly, but there were no jobs at that time. So I became a photographer for a newspaper. And that was very good training because you never knew where you were going that day, it was always an adventure. But at some point, the newspapers became more and more about photographing famous people who didn't even know why they were famous. That's when I didn't enjoy photographing so much anymore. Because the best thing is to photograph humble people. They can tell you much more about their surroundings. When you watch a film or talk shows with actors, they are often portrayed as ‘heroes’—but the real heroes are out there, in the real world.

MPB: Do you think living on an island has influenced the way you work?

RA: Yes, I think so. Because in Iceland you are part of the environment in a way. I always go out when the weather is bad, that makes for the best pictures in my opinion. So it makes you strong and you're no longer afraid of the weather. I felt a bit like Robinson Crusoe on a desert island. Nobody knew who you were. You could do your thing. And if someone didn't want to know about it, that's okay. You don't play guitar for cows, they can't clap either, so you play the song for someone who understands it. That describes my mentality quite well, I think. I just keep doing what I feel like I have to do and that is to document the conditions in the Arctic.

The Arctic is a difficult place. It's so cold and you need a lot of passion. Like many other photographers, I went to Africa to take pictures but felt like I was just copying everyone there. So I wanted to change my direction. I grew up in the cold, so that suits me better. You have to follow your heart when you feel like you're doing something that has meaning even though it might have more meaning in the future—a hundred or two hundred years from now—than it does today. Because some of the things I did can't be repeated. It's like painters from the 16th or 17th century. They weren’t necessarily as highly regarded then as they are today.

MPB: Was there a specific moment when you realised the seriousness of the climate crisis?

RA: It started when I photographed farmers in the fields at ten. I remember wondering what it would look like in fifty or a hundred years. Over time, I have also observed that things have changed. But I became aware of it in 1985. In Thule, the northernmost village in Greenland, I saw an old man sitting outside, looking up at the sky, sniffing the air and saying something I didn't understand. After five days, I found someone who could translate his words. He said that something was wrong. That it shouldn't be like that. That was when it dawned on me that the people knew what was happening. In a sense, they are walking on the pages we read in the books. So they are part of the book, part of the story. That's when I started looking at things more closely and documenting everything that could change.

A good example is the ice in the Arctic. I can tell a story about how, at one point, it was safe to walk on it, now it's not secure at all, and in twenty or thirty years, you'll be boating there. So, some areas are changing drastically.

MPB: What role do photographers play in documenting the climate crisis?

RA: They play a big role. I think photographs have already changed the world or opened people's eyes, like the picture of the girl running away from the napalm bomb in Vietnam. That changed the war. And there are many other pictures, like the poisoned water in Minamata, taken by Eugene Smith. Those kinds of photos and stories change things.

And I just try to make people aware of life in the Nordics and that people there should be concerned and given a chance. Many people say that they have nothing to do with it and that it's all happening somewhere else on the planet.

But I’m not preaching, I leave it to the scientists to tell us what is happening. But I think documenting the changes is very important because things are changing. I've seen it myself, and I still see it. But scientists have, of course, learned much more about it and can describe the circumstances more accurately. Still, photography and videography are very important, I think. In the coming years, all eyes will be on Iceland and the North in general, in my opinion, because of melting sea ice and shrinking places. Things are changing in front of our eyes. That’s undeniable.

MPB: What equipment do you use? Do you change your equipment often?

RA: Leica! I've been using this brand all my life, and I think the quality is great. I have used them down to -53°C [-63.4°F]. I always carry a lot of batteries, though, because they run out so fast. But the cameras always work. I’ve dropped my camera in the ocean before and things like that, and it’s always working, it’s a workhorse. So, I’m grateful that I get to use this brand. It’s like when you’re a fan of a music group or a football club, you’re stuck with it for life.

MPB: What does your creative process look like?

RA: I don't have a specific creative process. But I always feel like I have to do something. I always try to take at least one good photo. That is a lifelong task. It will drive me all my life. I also always like to compare photography to music. Paul McCartney, for example, wrote a song inspired by a song he heard on the radio. But his song sounded completely different.

In the same way, I get inspired by other photographers and artists. And then I try to do what feels good. But I also have this drive to get better and do something. And it's always important to stay humble. If you feel that you don't have to go out anymore because you are so great, that's it.

MPB: What have been the biggest challenges in your career so far?

RA: I always face the biggest challenges when moving, for example, in the Arctic Ocean. Is there a storm coming up that will make the return trip difficult? Will it be very cold, will the cameras work? I have also flown in very bad weather, sometimes I had to fight to get back. But the older you get, the more cautious you become. When you're young, you think you're immortal. You feel invincible. When I think back to that time, it strikes me that I did many stupid things and often fought against the elements in Greenland, Iceland and Siberia, and places like that.

Of course, the extreme cold is a big challenge as well. When you're wearing thick gloves, it isn't easy to take photos. Your eyes water, but you have to see what you are photographing. So, it can be very challenging.

MPB: Have you ever thought that it's all too much? If so, do you have any tips on how to keep going?

RA: Giving up is never an option for me. But I do weigh up whether travelling to certain places to take photos makes sense. If it seems too dangerous and the likelihood of getting great images is low, then I don’t do it.

MPB: Do you hope we can somehow mitigate the climate crisis?

RA: Well, our planet is in the phase of warming up, that's for sure. It's been warming up before, it’s been colder, it’s been warmer. So I don’t know, scientists will have to tell us. But we as people are polluting too much. So we have to be careful. But I’m still hopeful. Scientists are doing research at a very fast pace and will have more and more information every year. I believe that we can still solve this crisis. But we are almost eight billion people on the planet, which is quite a lot.

I listen to scientists and read about what they have to say, and I think they need a voice with the help of our pictures. Because I feel like they don’t get heard enough, even though they have much to say.

MPB: What are you working on at the moment?

RA: I am working more or less exclusively on the Arctic project. I’m going to Alaska and Greenland for example. I want to show what happens when people have to leave their villages because they can no longer hunt enough. They then have to move to bigger cities. That's interesting to photograph because it's happening now, and the images show why they are leaving. So that's part of the project. And this exhibition is also a step in the way of this project. I cover all eight Arctic countries, and it's a journey to all of these countries. They are all very different, but they also have a lot in common. They all have the same problems. The ice is melting fast. So, many different species and plants die or get sick every day. The world is changing. However, many people think that nothing is happening and that is very dangerous.

Read more interviews on the MPB content hub.