MPB Meets Alice Cazenave: The Darkroom Innovator Making Film Photography Eco-Friendly

Published 14 March 2025 by MPB

Behind every stunning photograph lies a hidden story—of chemistry, materials, and an environmental impact few consider. Alice Cazenave is a photographic artist and doctoral researcher with a passion for eco-friendly film photography. As the Sustainable Darkroom’s advisor, she helps develop innovative approaches to reduce the environmental impact of traditional photographic processes. From experimenting with plant-based chemistry to researching the ecological implications of silver extraction, Alice is dedicated to reshaping the relationship between photography and the environment.

In this interview, Alice shares insights into her creative journey, the inspiration behind the Sustainable Darkroom, and her hopes for a more ecological future in the photography industry.

Alice Cazenave

MPB: You have been working with the Sustainable Darkroom since 2020. Can you tell us more about what the Sustainable Darkroom is?

AC: The Sustainable Darkroom is an international charity dedicated to helping artists and educators adopt more ecologically conscious photographic practices. We aim to develop, research, and teach lower-toxicity methods for film and print processing while addressing the environmental and social impacts of traditional photography.

It’s also about highlighting the hidden environmental cost of photography and encouraging photographers to adopt more ecologically-minded methods without compromising creativity. While much of the responsibility currently falls on individual artists, we hope to inspire industry-wide change, urging manufacturers and institutions to engage seriously with the ecological footprint of photography materials and processes.

Our work includes running workshops on plant-based film development, organising residencies where artists can contribute to research on ecological photo methods and share their findings globally. During the workshops we work with plant-based developers: an ascorbate solution with added plants, which offers an ecological alternative in film processing. Ultimately, the Sustainable Darkroom is about more than just low-toxic methods—it’s about reshaping photography’s relationship with its history and fostering a culture of material awareness and care within the medium.

MPB: Was there a specific moment you realised analogue photography should be more ecological?

AC: My awareness of the environmental impact of film photography developed gradually. We're rarely encouraged to question things like why film needs to be washed in running water for an hour or where the materials, such as the metals used in production, actually come from.

Some of my first work looking at links between photography and ecologies was through Pelargonium printing—a method of printing onto living leaves. I exposed a leaf to light using a negative and stained the areas that had been exposed to reveal the photograph. That was my first step in blending plant life with photography and immediately sparked my curiosity about the agencies of plants as photographic materials. However, it was through meeting like-minded people and diving deeper into my PhD research that I truly began to grasp the ecological and social costs of traditional photographic processes—such as the pollution caused by extracting silver and transforming it into film. Manufacturing film is a really chemically intensive process.

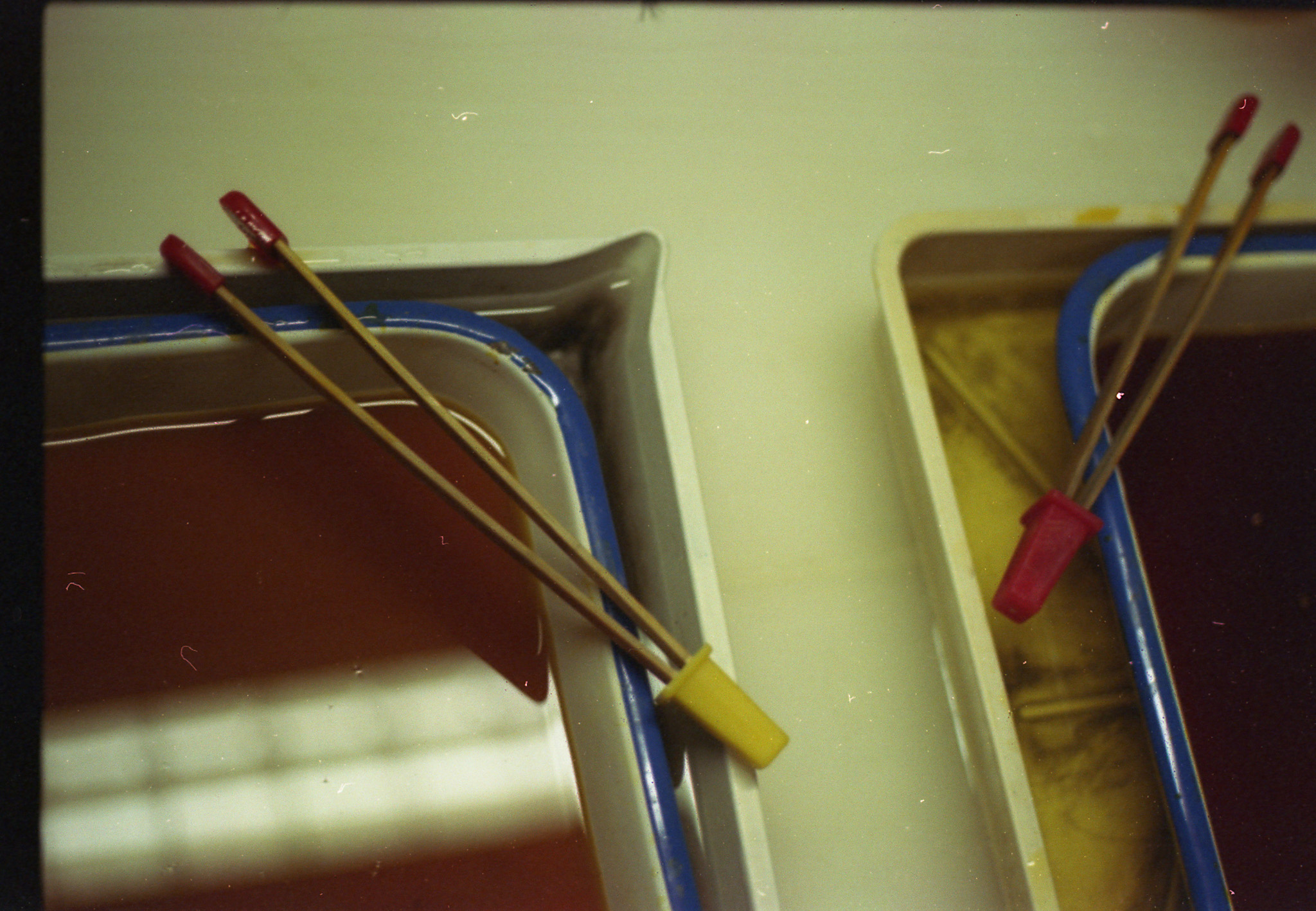

Darkroom trays with plant developer

MPB: Do you think your focus on more ecological methods has ever been a limiting factor on your creativity?

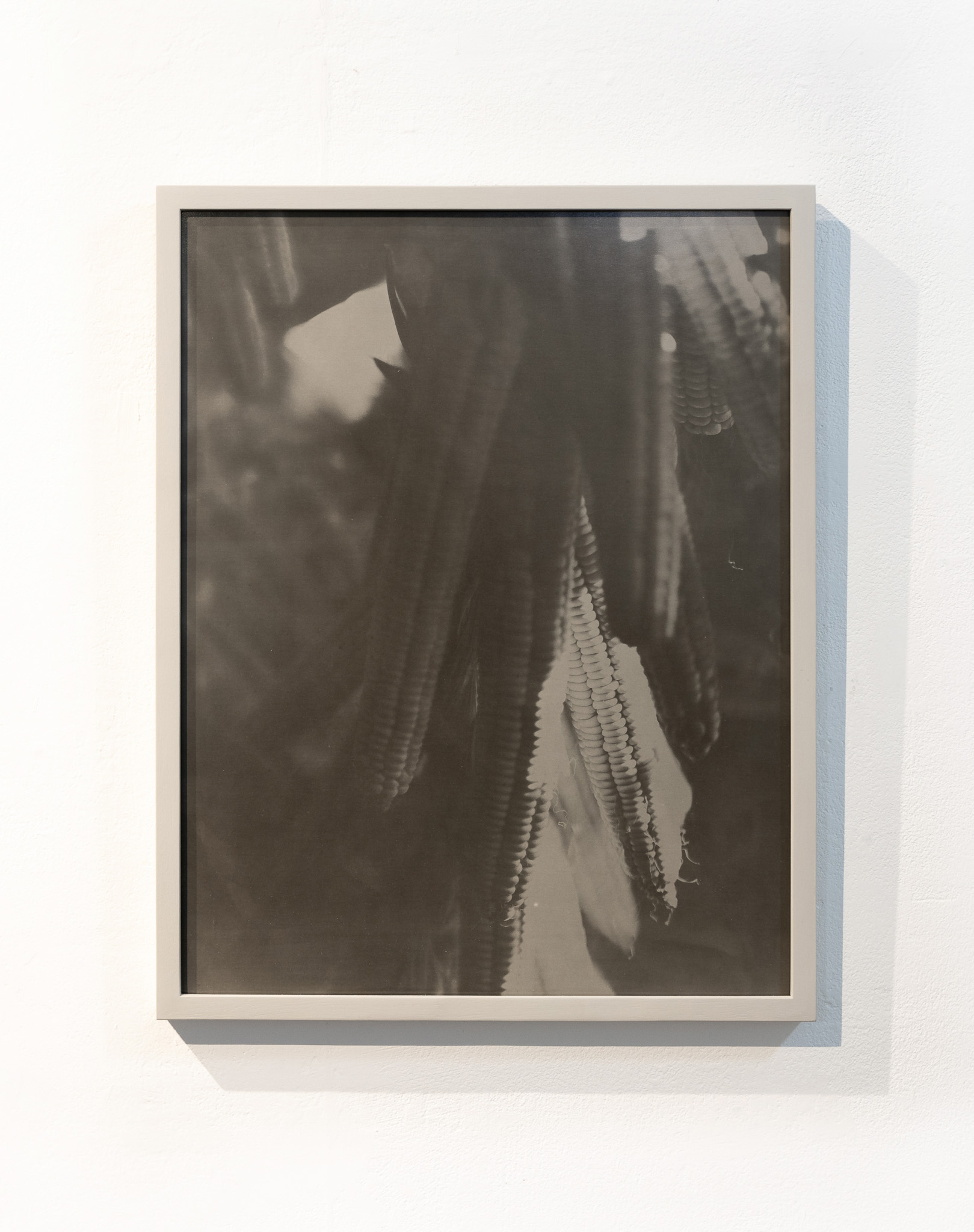

AC: Not at all—working this way has actually expanded my creativity rather than limited it. My creative process often involves thinking about how I can reuse materials, minimise waste, or find new value in discarded elements. For example, while working in western New York, I had the opportunity to collaborate with Kalen Fontenelle, a Seneca (Native American) photographer. We created a photograph of White Corn, which would have been cultivated extensively and with care by Seneca people before photographic industries arrived and contaminated their lands. We developed the photograph using a solution that is left over from cooking the corn, to acknowledge the toxic and colonial histories of film photography.

Experimenting with plants brings an element of surprise and discovery, as each has its own unique chemical properties and stories. Some photographers prefer to have total control in the darkroom, but I enjoy letting the materials guide me. Rather than being restrictive, working with plants to make photo-chemistry opened me up to new aesthetic possibilities that were only revealed to me by relinquishing control a bit.

a:yetíya' dágeha’ [We Should Help Her] in collaboration with Kalen Fontenelle

MPB: You mentioned your research is based in the US. Is there a specific reason for that?

AC: My research is based in the US because I’m investigating the metals, solvents, and contaminants involved in film production, with a particular focus on silver. Silver is essential to film photography, as silver salts make film light-sensitive, and without it, the process as we know it wouldn't exist. Given its importance, I’ve been exploring the colonial, social and ecological impacts of silver extraction and its use in film manufacturing. I’ve conducted research in Nevada and in New York, home to Kodak’s largest chemical manufacturing plant, to better understand the environmental contamination linked to the industry.

Eastman Business Park

MPB: What kind of gear and accessories do you use?

AC: My camera kit is pretty simple. I used to have a Pentax 6x7, which I loved, but it was heavy and, unfortunately, got stolen. Now, I shoot with a Yashica Mat medium format camera—compact and lightweight, and delivers great results. Decades ago my mum gave me a Canon AE-1, an indestructible and reliable 35mm camera, which I use a lot.

I’ve never been drawn to digital photography—it just hasn’t clicked with me. Like many film photographers, I’m taken by the tactile, material nature of film. Digital photography has its own physicality, relying on metals and energy-intensive storage, but it doesn’t offer the same experience of making something. My focus lies more in experimenting in the darkroom and working with chemistry rather than in taking photographs. Every photographer has their own way of working, and for me, the real draw is in the physical creation of the print rather than the act of shooting.

All About Plants

MPB: You mentioned using different types of plants in your chemistry—do different species produce different effects?

AC: Yes, different plant species can produce different effects. The combination of plant chemistry and paper often results in varied tones, with some combinations creating reddish-brown hues while others yield deeper blacks. The paper’s emulsion and the silver particles within it also influence the final outcome. In my experience, DIY photo-chemistry made with plants can produce softer, more subtle tones compared to industrial chemicals. But other times they work to the same standard, so it is a mix and often a surprise.

Plant developed film

MPB: When you talk about using plants, do you mean ones found at home or in the garden?

AC: Absolutely. I prefer to use plants that are readily available around me, it makes sense to do that over buying plants that have travelled across the world. I forage responsibly in public spaces, use garden plants, and work with a variety of plant parts—bark, roots and leaves—all of which can be used to develop black-and-white photographs.

I’ve worked primarily with plants growing in the US, in the research sites I've been working at. I was particularly interested in why certain plants were growing in contaminated spaces and what they were doing there. Some plants can help remove contaminants from the ground by mining metals back into their botanical matter, and I used those plants to create photographic developers. For example, in Nevada, where silver was historically mined for by photo-industries, I worked with desert plants that help stabilise mined earth by holding the soil together with their root systems. This was one way of foregrounding ecological narratives that are typically backgrounded in the stories we tell about photography and its history. Even everyday plants like grass cuttings and fallen leaves can be used, as most contain phenolic compounds that help develop images. Herbs like peppermint, rosemary, and thyme, which are rich in these compounds, are particularly effective.

Foraged plants

Unfiltered Change

MPB: How do you think sustainability is influencing the photography industry?

AC: Sustainability in photography is gaining attention, but much of the focus has been on capturing environmental issues rather than addressing the materials and processes used to create the work. It’s one thing to capture images of environmental degradation, but if the way you're producing those images is contributing to the problem, then it opposes what you're trying to do with the work. That’s something I think more photographers and institutions are starting to acknowledge. At Sustainable Darkroom, we encourage a deeper approach—rethinking everything from the chemicals used to how materials are sourced and disposed of. More photographers are exploring methods like plant-based developers and reusing expired materials. However, for meaningful change, the industry—particularly large manufacturers—needs to take responsibility and take meaningful decisions to reduce their ecological footprints. My hope for the future is to drive this industry-wide shift, ensuring sustainability is not just a trend but an integral part of how we think and move through this industry, and how the industry develops itself going forward.

MPB: How do you create awareness and get the international photography community to engage with ecologically-minded practices?

AC: We’ve built awareness and engaged the international photography community through exhibitions, workshops, and social media. Along with my colleagues Edd Carr and Hannah Fletcher, our work is being exhibited at major galleries like the Saatchi Gallery (London, UK) and Chappe Art Museum (Finland). This kind of institutional recognition helps push ecological photo-methods into the mainstream, where they belong.

Social media is a powerful tool for connecting with artists, and many are drawn to the allure of working with plants. But we try and make it clear that plants are not the complete picture - it's critical to dispose of chemistry properly and mainly reduce what you consume in the first place. Our publications, which document cutting-edge research into ecological methods, have also helped us reach artists worldwide, providing valuable resources to those who can't attend workshops in person. We also have a Patreon (a subscription-based platform) and Discord allow members of our online community to share their experiments, ask questions, and learn from each other—this saves a lot of time and labour when trying to work things out.

Making this material accessible is a core ethos, as well as helping people realise that they don't need to rely on industries they disagree with, which is hugely liberating.

Thank you, Alice (@alice_cazenave_, @sustainabledarkroom)! Read more inspiring interviews on the MPB content hub.

Climate Crisis Photographer Ragnar Axelsson

Read our interview with Iceland’s award-winning photographer Ragnar Axelsson on the importance of documenting change in the Arctic.

How to become a sustainable photographer

Sustainable photography is the way in which photographers can account for their ecological footprint. Simon Veith discusses how to develop a more sustainable photographic practice.

You can sell or trade your camera kit to MPB. Get a free instant quote, get free insured shipping to MPB and get paid within days.