Learn: 5 Differences Between CCD & CMOS Sensors

Published 6 January 2026 by MPB

The sensor is one of the most important—and often misunderstood—part of any digital camera. The vast majority of cameras use either a Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) or Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor (CMOS) sensor.

Around the mid-2000s, camera manufacturers began phasing out CCD in favour of CMOS sensors. But what’s the difference between CMOS and CCD sensors? Why are some photographers turning to older cameras with CCD sensors? In this article, we’ll explain the history of the sensors, their benefits and drawbacks, and how they affect images—including everything from rolling shutter and video to exposure and colour rendition.

Up to the early 2000s, most compact cameras had a CCD sensor. Not just digital compact cameras, but pretty much any digital camera. Since then, CMOS sensors have superseded their CCD counterparts. However, CCD still has a huge following among some photographers who believe in the superiority of the images produced by this older technology.

Ian Howorth | Leica M9 (CCD)

The popular notion is that CCD sensors produce more filmic, organic-looking images, while CMOS images are seen to be more clinical and lacking character. But how much truth is in that theory?

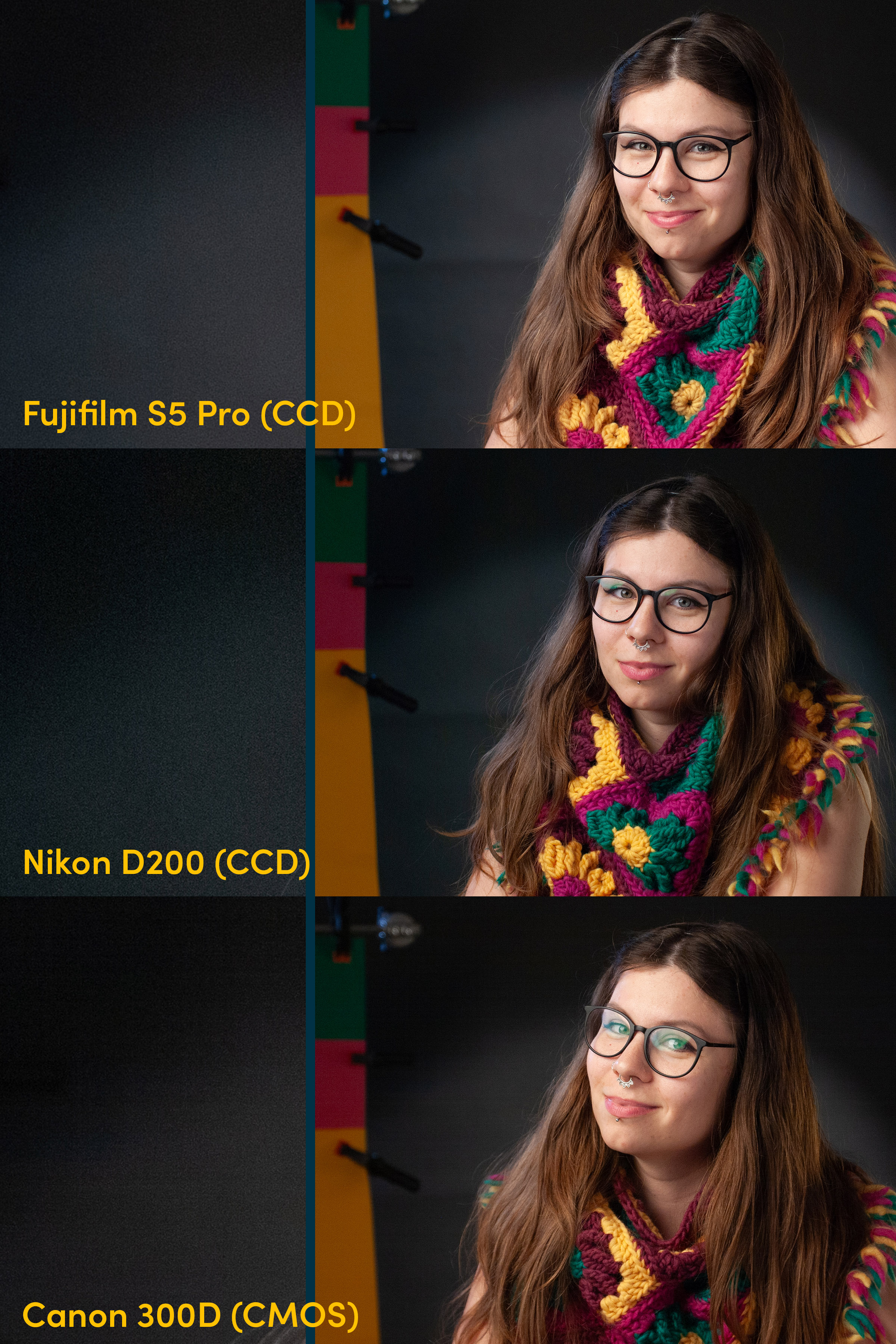

We took a series of photos in a controlled studio environment to compare the images produced by both sensors. We used cameras like the CCD Fujifilm FinePix S5 Pro, Nikon D200 and Nikon D80, the CMOS Canon EOS 300D and Canon EOS 400D, and the Sony A7S III.

Used Nikon D200 (CCD)

About CCD & CMOS sensors

First, let’s look at how CCD and CMOS sensors work differently. At the start, capturing a photo—in both CMOS and CCD sensors—is the same. Light particles hit an array of photo-sensitive cells, producing electrical charges. The difference is how the sensor reads data and converts it into a digital signal. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages.

Connor Redmond | Olympus µ-mini (CCD) | 5.95mm | f/3.5 | 1/30 sec | ISO 125

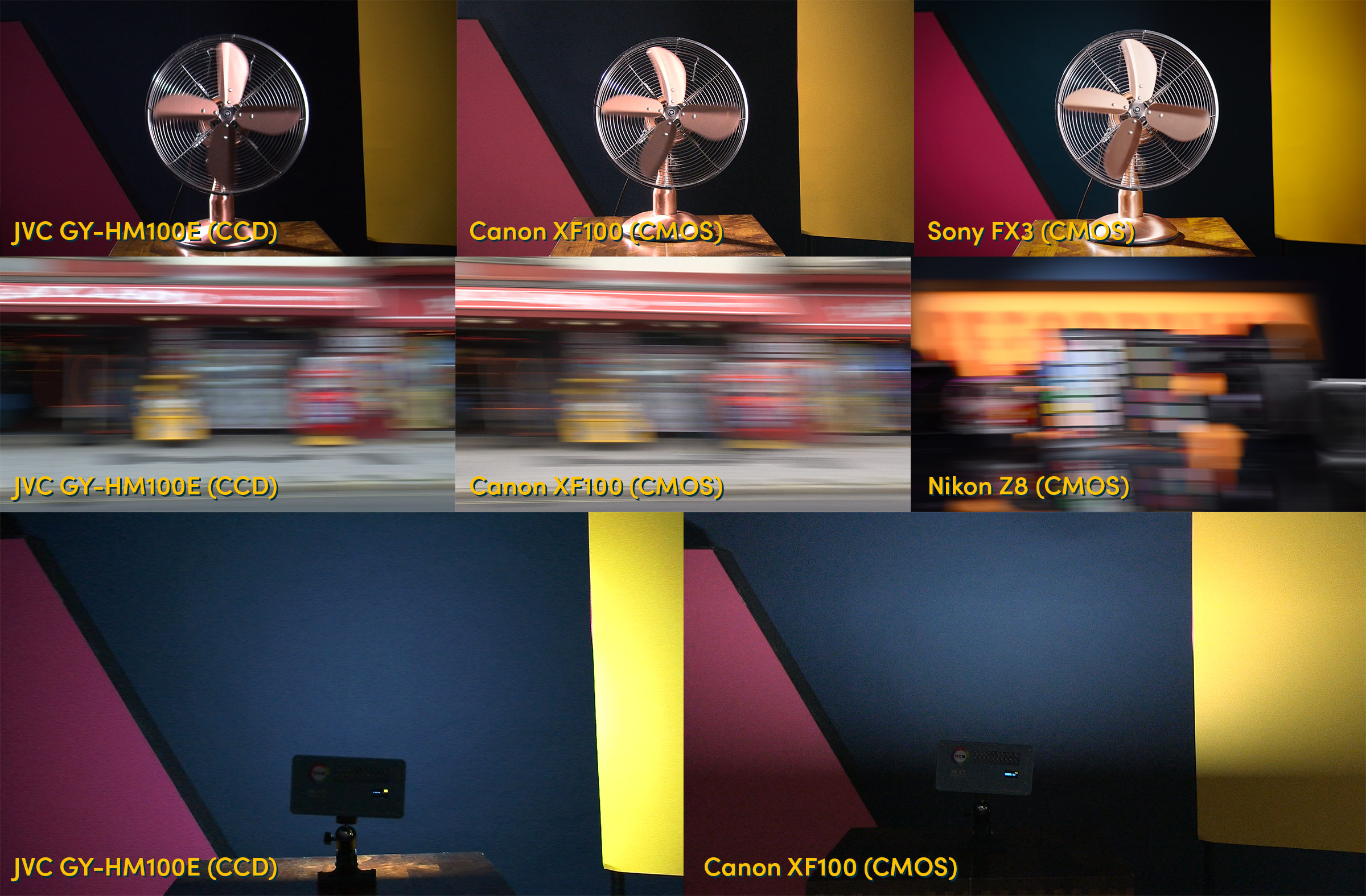

Vertical smearing

When a CCD sensor captures an image, the charge transfers vertically along a line of pixels through a series of capacitors. Once they reach the edge of the sensor, the charge reads out. If the scene includes a light source that is too bright, the charge won't complete. This results in excess charge gathering in the affected rows and causes the appearance of vertical smearing. You can see an example of this issue below.

CMOS sensors, on the other hand, read out each pixel individually—the charge doesn’t transfer along rows. The readout process is faster, too, so there's less chance of incomplete charge transfer. Therefore, CMOS sensors are far less susceptible to vertical smearing.

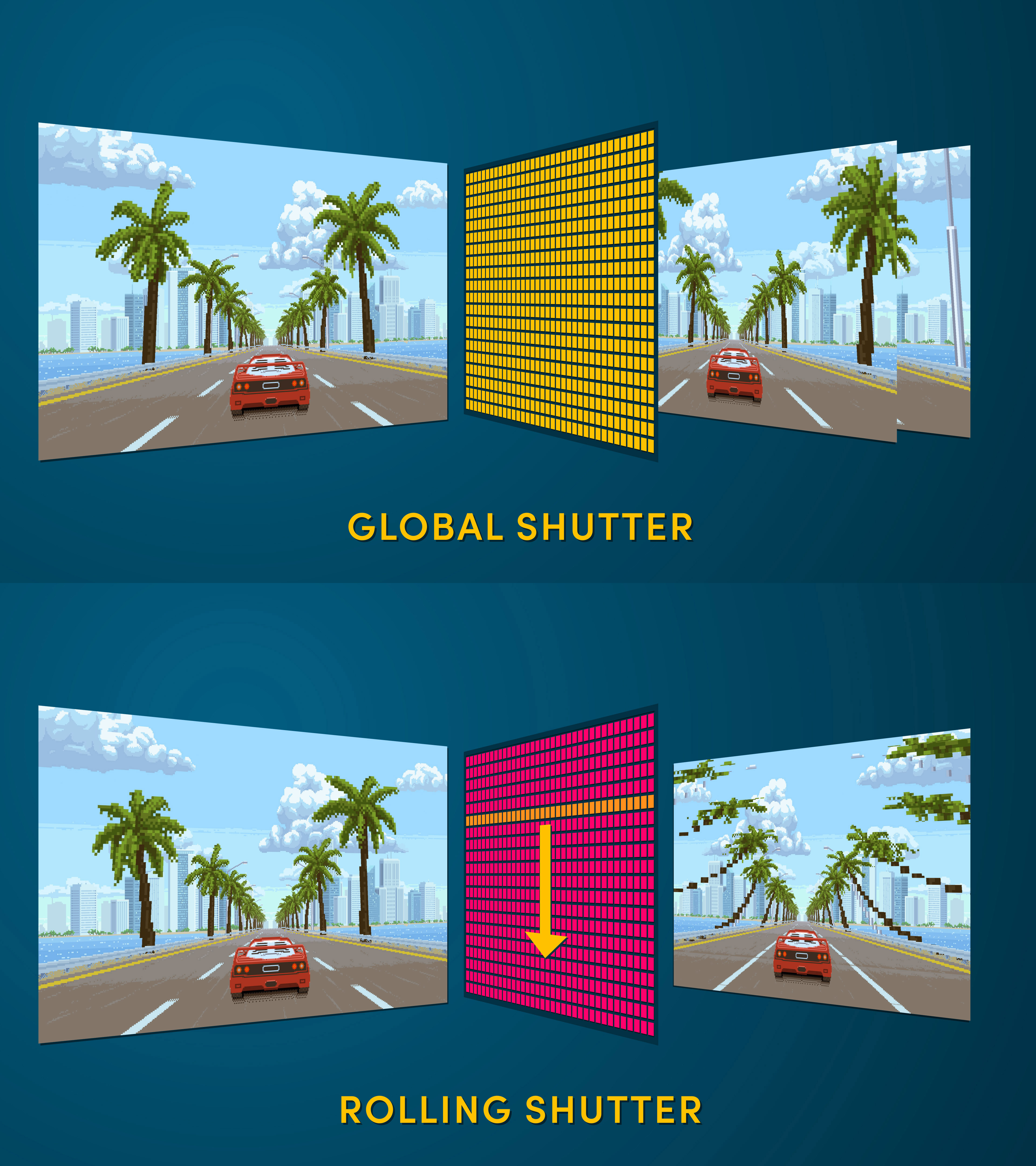

Rolling shutter effect

The ‘rolling shutter effect’ is infamous for creating distortions in fast-moving subjects. Rolling shutter affects both stills and video footage—most noticeably when using higher shutter speeds on mirrorless cameras with an electronic shutter. Rolling shutter still appear on mechanical shutters, but it’s usually less noticeable than on mirrorless.

With CMOS sensors, before the camera finishes the sensor readout, the objects in the frame have already changed their position. This effect can be visible when filming fast-moving objects, doing quick pans or filming flashing lights.

Usually, CCD sensors use a global shutter, which exposes the entire sensor to light—all in one go. The read-out is simultaneous, too (albeit along rows). These two factors help to reduce any rolling shutter effect in the final images.

These days, some cameras—like the, Blackmagic Design Production Camera 4K EF and Ursa Mini 4K EF—have global shutter CMOS sensors. The first global shutter, full-frame CMOS sensors are now making their way into widely available digital cameras, like the Sony A9 III.

Pattern noise

The most apparent difference for me is in the noise pattern. Heavily underexposed areas on the early CMOS-based cameras have a strong fixed pattern noise. It is much more pleasing and organic looking on the CCD cameras.

Digital noise in underexposed areas | Model: Ewa

Exposure

The CCD cameras also handled overexposure slightly better. We brought the exposure down by two stops. While you can see the clipped highlights, they look a little better on the CCD cameras.

But if you look at a photo taken on a modern CMOS sensor, it handles both under- and over-exposure well. This really does show the advancement in CMOS technology.

Photos overexposed by 2 EV and brought to correct exposure in Adobe Lightroom | Model: Ewa

Colour rendition

Besides the older camcorders, there are a few cine cameras—equipped with a CCD sensor—praised for their ‘filmic’ image quality and ‘organic’ grain. These cameras include the unique Digital Bolex, Ikonoskop A-Cam and Sony F35.

Jakub Golis | Fujifilm FinePix S5 Pro | Nikon AF-S DX Nikkor 35mm f/1.8G | f/4 | 1/30s | ISO 100

In terms of colour rendition, it’s similar to modern cameras. Images from Canon are slightly warmer than those from Nikon. Images from CMOS-based Canon cameras appear more saturated in RAW (with default settings) and JPG. Editing them doesn’t take long, so they look almost identical

It looks like it has nothing to do with a sensor inside a camera. Instead, it’s all about the manufacturer’s approach to rendering colour.

Model: Nell (@dragmetonell)

CCD sensors in technical imaging

There are only a few areas of scientific and technical imaging in which CCD sensors have, up until recently, had the advantage over CMOS. CCDs were used, for example, for extreme low-light and near-infrared imaging. These days, tech advancements have allowed CMOS sensors to achieve similar or even better results—but CCD technology is still in use for technical imaging.

Jakub Golis | Leica S2-P | Leica Elmarit-S 45 CS| 45mm | f/2.8 | 1/500 | ISO 160

Verdict: The Magic of CCD Sensors

There are objective and subjective differences between the CCD and CMOS sensors. These differences aren’t so much about colour—as these are adjustable in the edit.

Due to CCD sensors’ limited dynamic range, they protect the highlights. Therefore, CCD images appear darker and more cinematic. Plus, the lower resolution makes the images softer, less sterile and more film-like.

But when using CCD and CMOS sensors, the main difference is the nostalgia and the experience of using outdated, less-perfect technology. Many CCD photographers don’t care about the sensor itself. Instead, they’re seeking the quality of the images and the nostalgic vibe.

Jakub Golis | Nikon D80 – SOOC JPG | Nikon AF-S DX Nikkor 35mm f/1.8G | f/1.8 | 1/1000s | ISO 100

Why else do CCD images look filmic? In the early days of digital cameras, manufacturers tried to make digital photos look like film. For example, the earlier digital Leica cameras mimicked the look of Kodak Kodachrome. At the time, film was still the ‘superior’ medium—and photographers were just used to a specific look.

Today, regardless of the reason, there’s certainly something inspiring about using older technology—and embracing all of its imperfections.

Jakub Golis | Leica M8 | Leica 35mm | f/8 | 1/180s | ISO 160

Shoot JPEG only? You may find the output of many CCD cameras more pleasing. But you can get great straight-out-of-camera images with many modern CMOS cameras, especially the ones with robust JPG adjustment options like Fujifilm or Olympus.

If you shoot RAW, it’s easy to edit your images to make them look more ‘filmic’—in which case, a CCD sensor won’t give you any rational advantage over CMOS.

Used Canon Powershot G7

Photography isn’t just about the scientific facts. It’s important to remember to have fun. So, if a CCD camera inspires you, grab one and start shooting. Any camera can be a great tool in the right hands.

Looking for more content about older tech? Check out our article about Hasselblad XPan alternatives, or read more gear guides on the MPB content hub.