MPB Meets: Black Lives Matter Protest Photographers

Published 10 September 2020 by MPB

The Black Lives Matter movement emerged in 2013 in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who shot and killed Trayvon Martin. It gained widespread momentum following the deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and many others at the hands of law enforcement. Advocating for an end to systemic racism, police brutality and racial injustice, the movement demands change through policy reform efforts, grassroots organising and protests. In the early 2020s, protests gathered momentum across the United States and around the world. Photography played an integral part in documenting these protests, as well as making police violence and injustices visible to a far greater audience.

In the summer of 2020, MPB spoke with five photographers who documented the protests in New York City.

https://youtu.be/VG8dxggYqtg?rel=0In this article, we hear from photographers Tahiti Abdul, Aaron Agyapong, Roger S. Echegoyen-Araujo, Duane Garay and Andy Jeronimo.

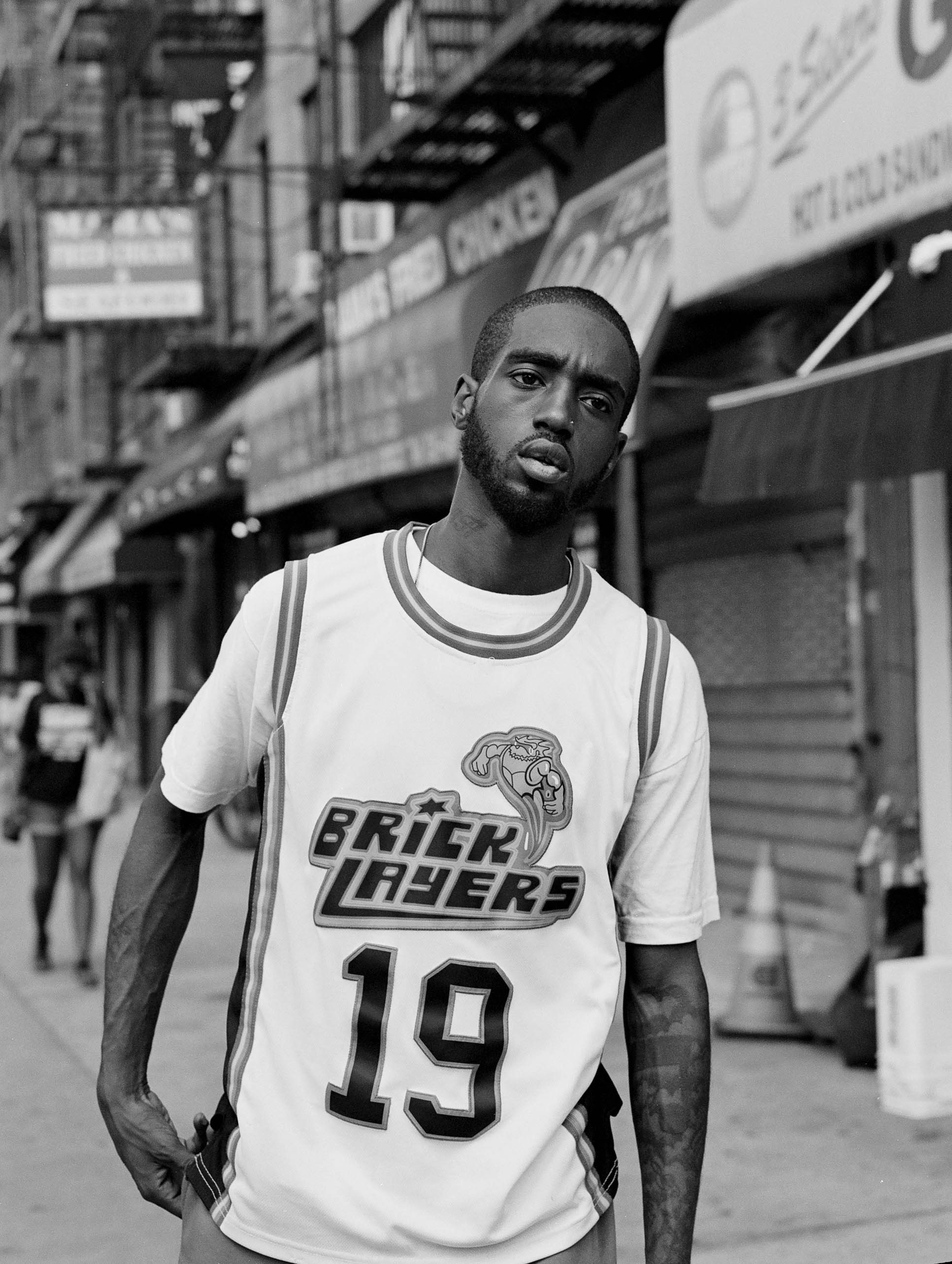

Tahiti Abdul

Everyone has a different opinion on how you capture a photo. But I think it's the story behind that photo is what's most important, to me at least.

I'm there to listen first and then it's a matter of just watching moments happen. And knowing when it's appropriate and when it's not appropriate to take your camera out and photograph things, because not everybody's there to be photographed.

Some people feel like faces should be blurred in the photographs. I'm not of that belief. So, when I attend protests, I tend to shoot it in black and white. I can control the contrast and the exposure a little bit better, than you can do on colour. Just to give that discretion to protesters, but at the same time, not hide the work in any kind of way.

But the colour photographs, for me, are to really put the subject on display. So I'll have those colour images, like from the Puerto Rican Day Festival, where I want to show the different styles, the clothes and the bright colors on the flag.

It's all thoughtful. At the end of the day, I'm not attending these protests with the sole purpose of photographing people, and looking for that shock value with my photographs. I'm there to see moments happen, but I'm mostly there to be a participant in the movement. And then the photos come with that.

My creative inspirations? Honestly, it’s my city, it’s the people around me, it’s the everyday movement. I know we don’t have much of that right now due to circumstances, but honestly, it’s just roaming around this city within the five boroughs.

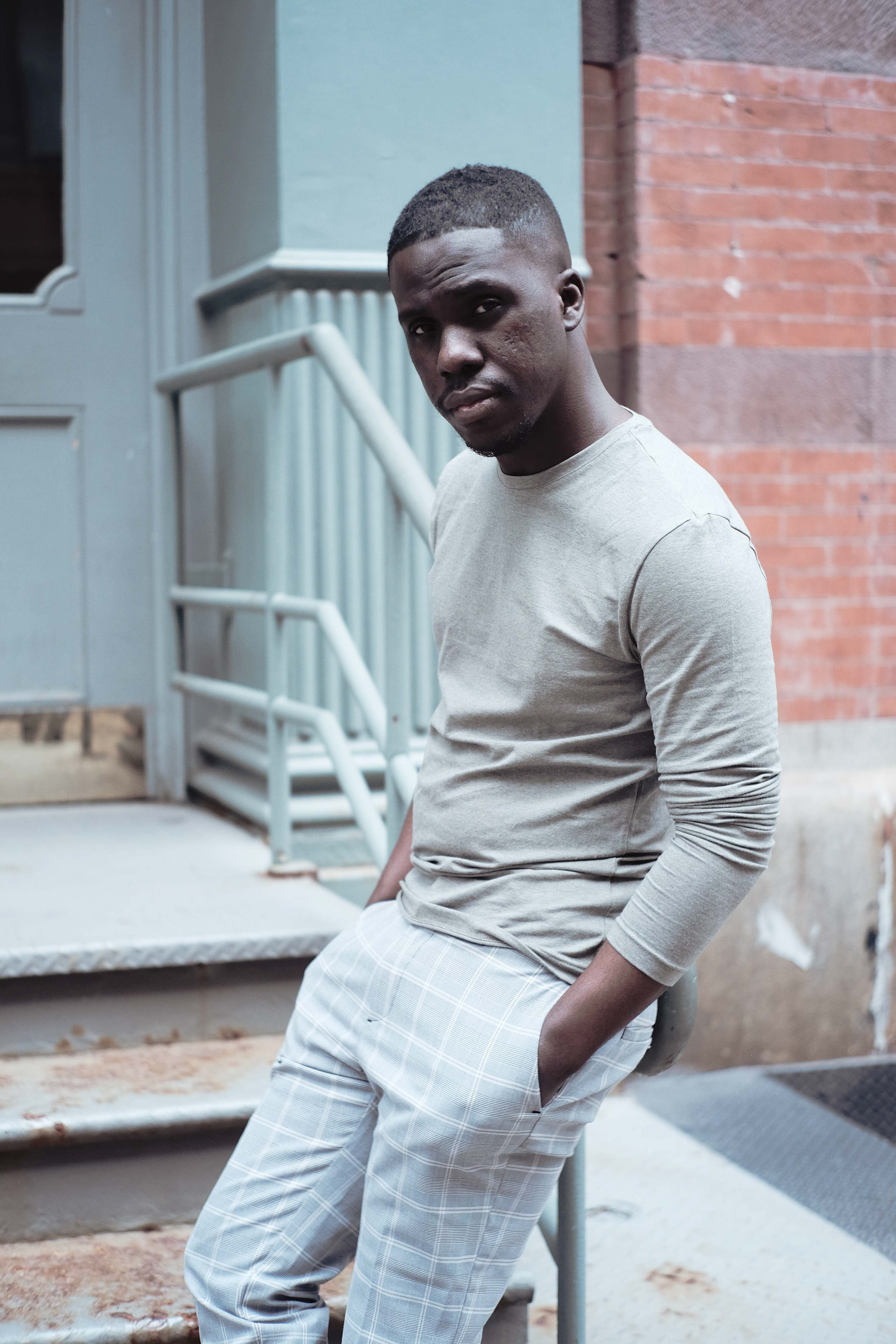

Aaron Agyapong

I was able to capture the truth as to what was going on. The protests actually gave me a better understanding as to how things really work, because when you watch it on TV, it’s more of a story that they’re trying to give you, but when you’re in the moment, you actually have an open mind as to what’s going on. You actually get to understand how people are feeling.

As a portrait photographer, you get a sense of how people are feeling, and I was able to see that—some people were angry, some were sad, and some were confused. I was able to capture that in the moment. I was shooting with my Fujifilm camera and then used my presets to color grade it, giving it an orange tone for a more old-school feel. That was my main focus.

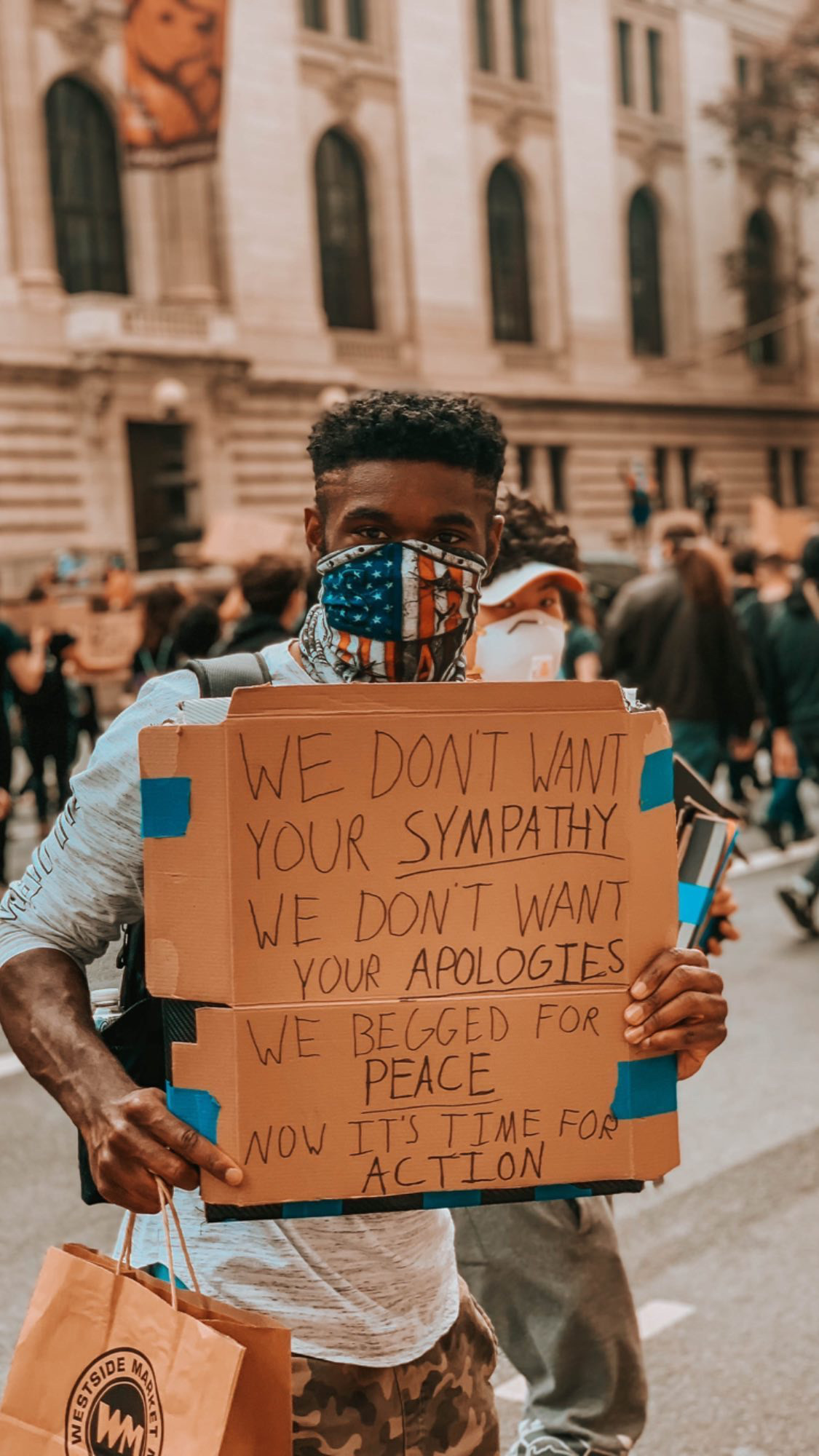

Roger S. Echegoyen-Araujo

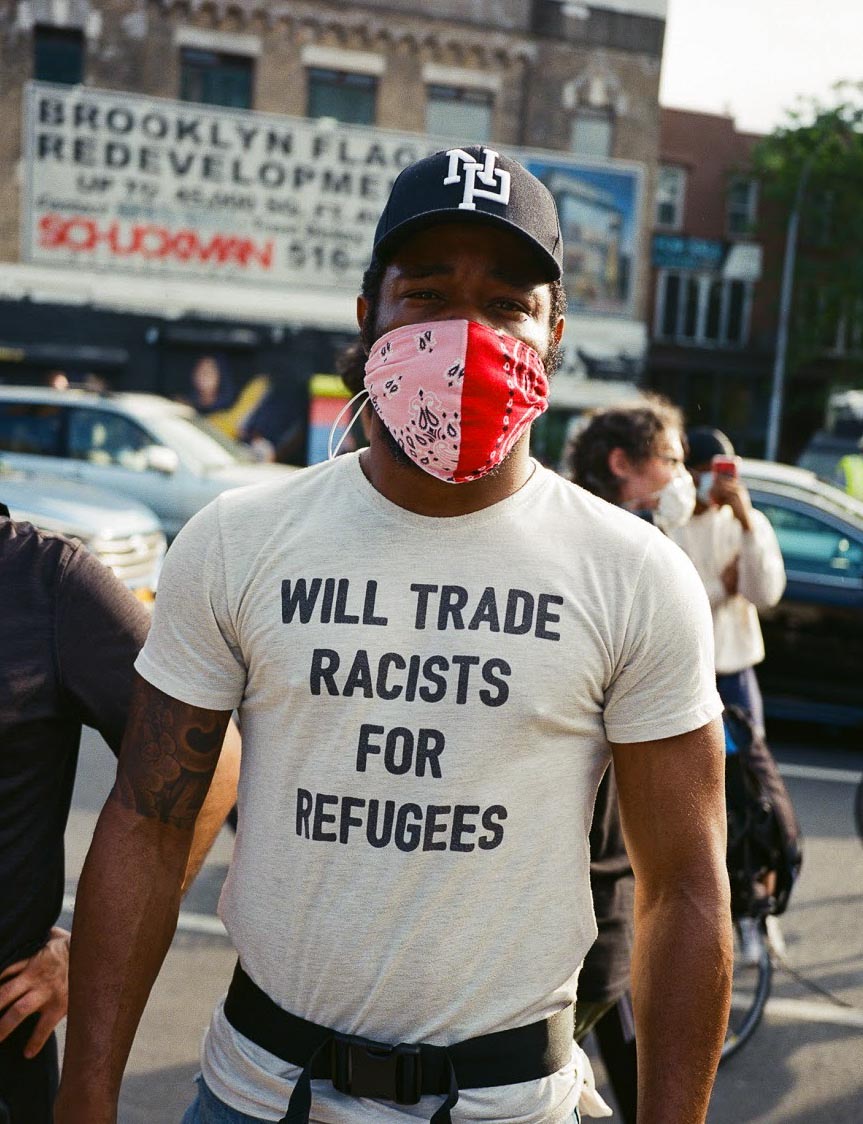

The way I try to shoot it is to just try to get a vibe of the crowd. If I feel like there’s enough of a kind of presence, in a sense, or there’s a lot of people kind of speaking but without really speaking — either through their attire or the way they’re dressed or what they’re trying to showcase — I’ll try to do more of the portrait shots.

I use two different cameras. The Fujifilm GA645 for my medium-format work because it's a little easier to handle in a crowd. And my Nikon F3. If I want to get a wider pictorial frame, I’ll use my F3.

You have to be incredibly sensitive, and at the same time, you don’t want to just glamorise a protest. You have to showcase it for what it is and what it stands for.

Duane Garay

They were natural. I wasn’t running around chasing for protest photos. It’s just like I normally have my camera with me — I have my camera in my bag right now — and I went to these things to be amongst my peers and there were moments that I really felt like should be captured, should be photographed.

My initial inspiration came from Time magazine, Life magazine, Gordon Parks, Jamel Shabazz and Roy DeCarava. Those were the images that really stuck with me. There's something emotional about black and white photography. Black and white is it for me—always, forever.

One of the things about the police photos is that there's a personal connection because half of my immediate family is in law enforcement. In our household, we have numerous heated conversations regarding the relationship between communities of colour and police officers.

One element I wanted to capture in those police officer photos is that a good majority of them are people of colour. It’s a complicated relationship. Those images are the ones I really enjoy the most because they capture a lot of emotion—or the lack of it. They definitely had an 'us versus you' mentality, and you can just read it in their eyes.

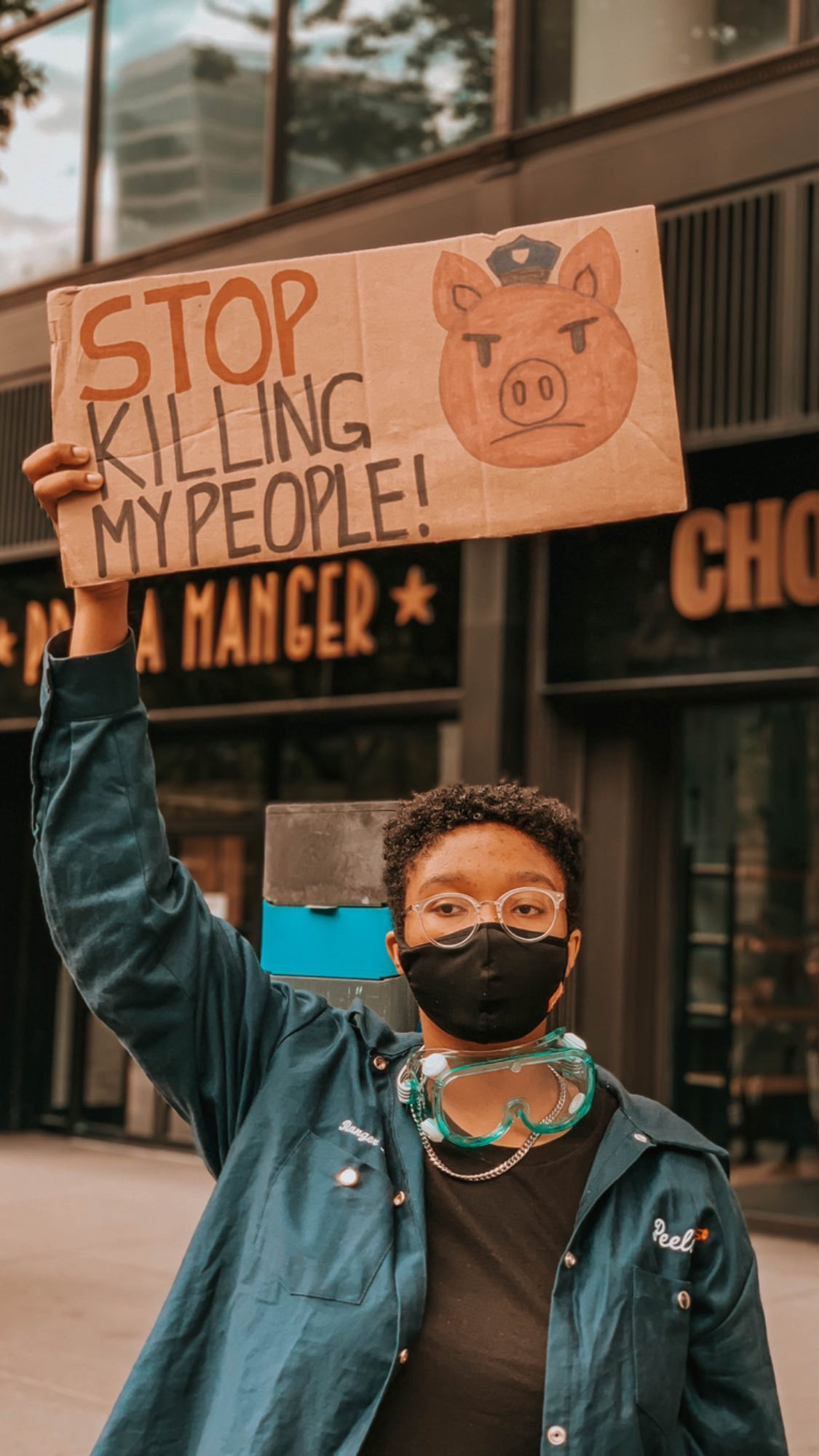

Andy Jeronimo

I’m from the Bronx, born and raised. I mainly started shooting street photography here in New York City because I wanted to focus on showing what the city really looks like. Growing up in New York City, it’s kind of hard for kids to really see the beauty of the city.

I approached it the same way I shoot street photography, but it was definitely different in the sense that you hear thundering loud voices, all yelling to be heard. It was shocking—very intense, to say the least.

I wanted to capture faces and emotions within the people I saw in the streets. Every face has a story to tell, and I wanted to capture that. I just like to load the roll and shoot—shoot away.

Read more interviews on the MPB content hub.